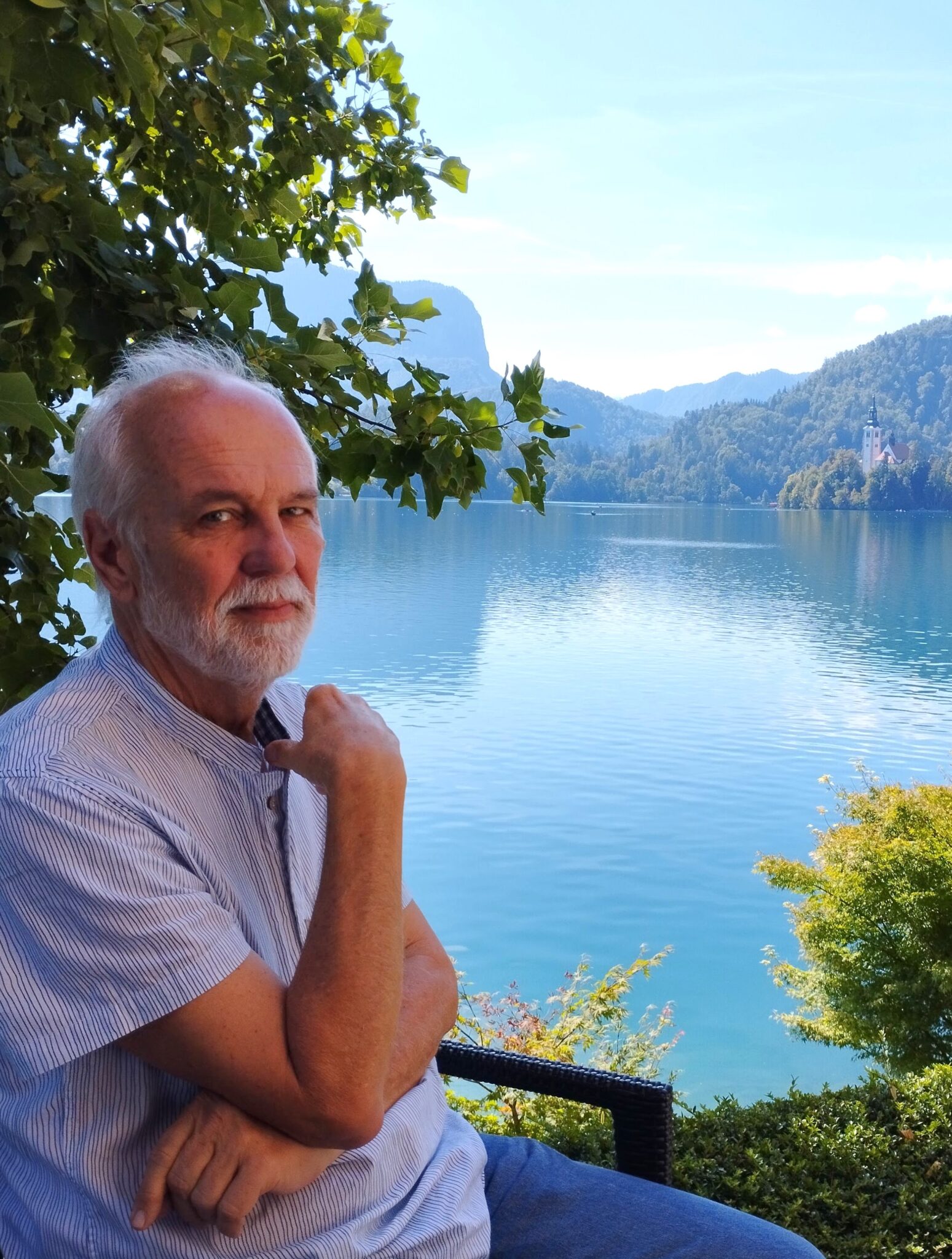

Darko Radović

Darko Radović is an Australian, born in the former Yugoslavia. He is Emeritus Professor at Keio University.

He practiced architectural and urban design and taught at several universities, including his alma mater, the University of Belgrade and the University of Melbourne, before coming to Japan as a researcher at the University of Tokyo in 2006. In 2009, he became a professor of architecture and urban design at Keio University, Faculty of Science and Technology, building upon what Kengo Kuma has started there. His research laboratory, co+labo Radović (an abbreviation of words “collaboration” and “laboratory”, connected with a significant “plus” sign) focused on intersections between environmental and cultural sustainability and the quality of life. co+labo still operates at Keio University, now under the leadership of Professor Sano Satoshi. Over the years, it has became the hub of an international network that includes a wide circle of academics and professionals from Japan and abroad. Most recently, with Professor Davisi Boontharm, Darko Radović has co-founded co+re.partnership, an international platform for strategic thinking making and living better cities, with regular engagements and collaborative projects at universities and other institutions in Asia and Europe.

Major publications:

Bilingual – Japanese/English:

『In the Search of Urban Quality:100 Maps of Kuhonbutsugawa Street, Jiyugaoka』(flick Studio and IKI)/『Subjectivities in Investigation of the Urban: The Scream, the Shadow and the Mirror』(flick Studio and IKI)/『Mn’M Workbook1: Intensities in Ten Cities』(flick Studio and IKI)/『small Tokyo』(flick Studio and IKI)/『infraordinary Tokyo – right to the city』(Shinkenchiku a+u)/

In English language:

『eco-urbanity – towards well-tempered environments』(Routledge)/ and other.

In an e-mail thanking Kengo Kuma for his invitation to join the illustrious Kuma-no-Wa, I asked which focus should I chose to best respond to his initiative. His typically succinct answer was: “Please tell about the importance of environment.” That suggestion to deal with broader context of this project refers to earlier discussions, including those associated with dramatic realities experienced during the outbreak of Coronavirus, realisation of drastic vulnerability of the humankind and of the established, seemingly unquestionable ideologies that shape dominant frameworks of our lives.

The question of words

Before discussing it, we need to ask what do we mean when we say environment, what environment is?

Words capture and communicate meaning. Etymology explores their “true”, original sense, but it can also point at ways in which the times we live alter those meanings. The origin of our keyword, thus, dates back to 1660s and early French environs, which simply referred to something around us. Two hundred years later the Latin suffixment, indicating action was added to create the word environment. From colonial France, via imperious British English and, eventually, American simplified “Globish”, that word became part of today’s common Lingua Franca.That continuity points at deeply ingrained understanding that environment is around us. Similar is the situation with Japanese 環境, kankyō. Common definitions of environment tend to refer to natural, physical phenomena (such as air, water, land, flora, fauna) which surround – us. Such externalising of the humankind has lead towards an ultimate, damaging anthropocentrism.

Anthropocentrism is another important word. Edmund Husserl found that the threshold towards that sense of superiority was crossed at the very beginning of the Modern Era, “in Galileo and Descartes, in the one-sided nature of the European sciences, which reduced the world to a mere object of technical and mathematical investigation”.

But for Milan Kundera, Cartesian understanding of man as “master and proprietor of nature” only points at the failure on that path, how, “having brought off miracles in science and technology, this ‘master and proprietor’ is suddenly realizing that he owns nothing and is master neither of nature (it is vanishing, little by little, from the planet), nor of history (it has escaped him), nor of himself (he is led by the irrational forces of his soul). But if God is gone and man is no longer master, then who is master? The planet is moving through the void without any master.There it is, the unbearable lightness of being.”

That superficiality of the dominant power encapsulates the reality we are living in.

To change that situation, to cancel an obviously erroneous way, the usage of the term environment needs to be carefully (re)qualified, again by emphasizing – action. This time that must be action of a very particular kind. What is now known as “environmental awareness” has started to emerge only in the late 1950s, when ecological and social sciences started to introduce and spread informed understanding about damages inflicted upon the physical and social fabric of places which we make and inhabit, by implementation of the narrowly defined “progress”. A resulting cry was embedded in inclusion of the mobilising, critical term – crisis!

While by “crisis” we habitually refer to “any event or period that will lead to an unstable and dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, or all of society”, etymology yet again points at complexity. That term, which has reached European languages in the early 15c, has originated in Greek krisis, and it contains one significant difference in relation to the present, global usage. The original (stemming from even deeper, Proto Indo-European roots) refers to a turning point, to judgment and action which can, and which are meant to make qualitative difference. Thus, crisis is a “vitally important or decisive state of things, a point where the change, for better or worse, must come. That includes responsibility. An imperative to judge what is right and what is wrong, and need to act accordingly have played the key role in rebellious and, importantly, international 1960s, in almost successful years of awakening, of emergence of an understanding of political, ideological roots of environmental socioecological crisis – not as a mere choice, but as a imperative for responsive and responsible action.

In his introductory interview for Moction.jp, Kuma points at insight facilitated by epidemics, ending by an explanation how using wood is “not a question of whether to improve efficiency or use wood, but rather to think about the fact that our definition of efficiency itself is changing” (my italics). Definitions, accepted meanings of words which we use, ask what is of critical importance for the broadest theme of environmentally and culturally responsive and responsible development: who defines the meaning? Who has the power to impose definitions, and in whose interest the dominant, seemingly unquestionable ones are?

As Thomas Kuhn used to explain, when “constructing a new paradigm, we cannot use the tools developed by the old paradigm, because even the questions asked were – the wrong questions.” In order to judge, one has to develop a clear, well grounded and well-defined critical position, strong enough precisely to question.

With no space to expand upon that theme, a list several book titles (a biased choice, organised alphabetically, by author) can provide the flavour and hint at their relevance (which, alas, has not diminished over time): Society of the Spectacle (Debord, 1967); Limits to Growth (Club of Rome, 1972); The Critique of Everyday Life (Lefebvre,1947); Urban Revolution (Lefebvre, 1970); The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement (Naess,1973) …

The way of wood

In that sense, although Kuma’s initiative is very specific, I also understand it as a much broader call to action, as an urge to seek new ways of looking both at usually separated, quantifiable, “exact” aspects and non-measurable,deeply human dimensions in thinking, making and living spaces – triggered by multilayered reinvention of wood.

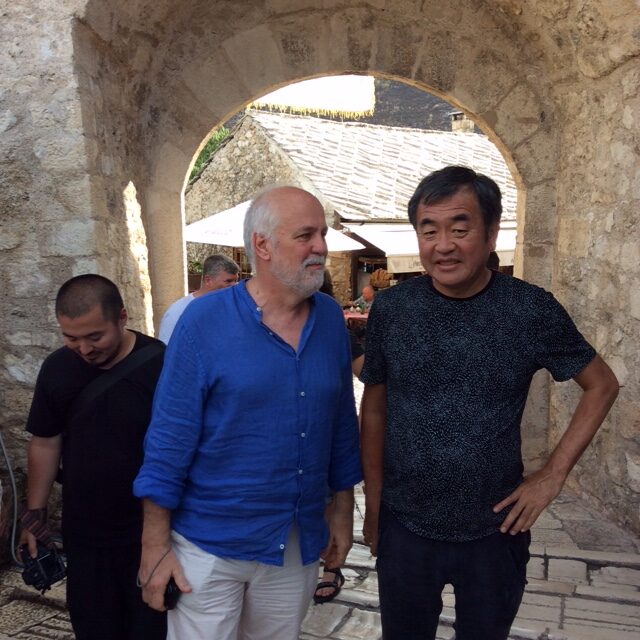

Our discussions of these issues are not new. In 2007 I had an opportunity to invite a group of leading academics and practitioners of architecture, landscape architecture, urban design and urban planning from Australia, China,Denmark, India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Singapore, Spain, Thailand and the UK to the University of Tokyo CSUR,to participate in the eco-urbanity symposium. Among invited colleagues and friends was Kengo Kuma.

At the symposium and later in the book eco-urbanity hypothesis: Towards well-mannered built environments (Routledge,2009), under the title “Bringing back nature and re-invigorating the city centre” he argued in favour of bringing back nature and history to the city. His opening position, with rich references to actual KKAA projects, was that an effective method of bringing nature back is to use natural materials.

That, again seemingly simple argument was based on an irony: the reader was reminded that Tokyo used to be a city where architectural expression was produced by limitations of its key building material – wood. As all natural materials do, wood embodies specific positive restrictions that contribute to the definition not only of architectural, but overall urban character. They determine the scale of the architecture and the streets and they ultimately generate human-sized environments.

Kuma invited us all to see the entire architectural culture of Tokyo as born from the restriction of the qualities of the wood with which it was built. His point was that, with the introduction of concrete, such restrictions disappeared and, as a result, the character of Tokyo was ruined, the human scale was lost, and the humane substance of Tokyo was all but destroyed. Reintroducing wood into the city can start bringing hope for regenerating some aspects of Tokyo’s own culture. That certainly is the case at architectural scales, but a similar logic also applies to urban life.He proposed that, while the main themes for urban planning in the 20th century were expansion and functional zoning, for the 21st century it should be the reproduction of rich, multi-purpose spaces that bring together a variety of central urban functions.

That was fifteen years ago. Kengo Kuma’s 2023 initiative elevates that logic to a higher level, the most promising aspect of which is in generous support by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, along with many other stakeholders. That support brings the much-needed sense of realism, even an air of pending paradigm shift in production of environmentally and culturally responsive and responsible, environmentally and culturally sustainable spaces. Kuhn has explained: paradigm shifts come suddenly; they are revolutionary and they change the world.

At that, broader level, the main task of our eco-urbanity team in 2007 was to cross common disciplinary and cultural boundaries, to think together and seek a better understanding of what constitutes sustainable practice today. We argued that such a practice should be capable of simultaneously embracing environmental responsibility and cultural responsiveness. That it should be locally accountable and thus globally relevant, and facilitate both thinking and acting in the direction of what we called theory of eco-urbanity and later, at Keio University, sought to implement as the practice of radical realism.

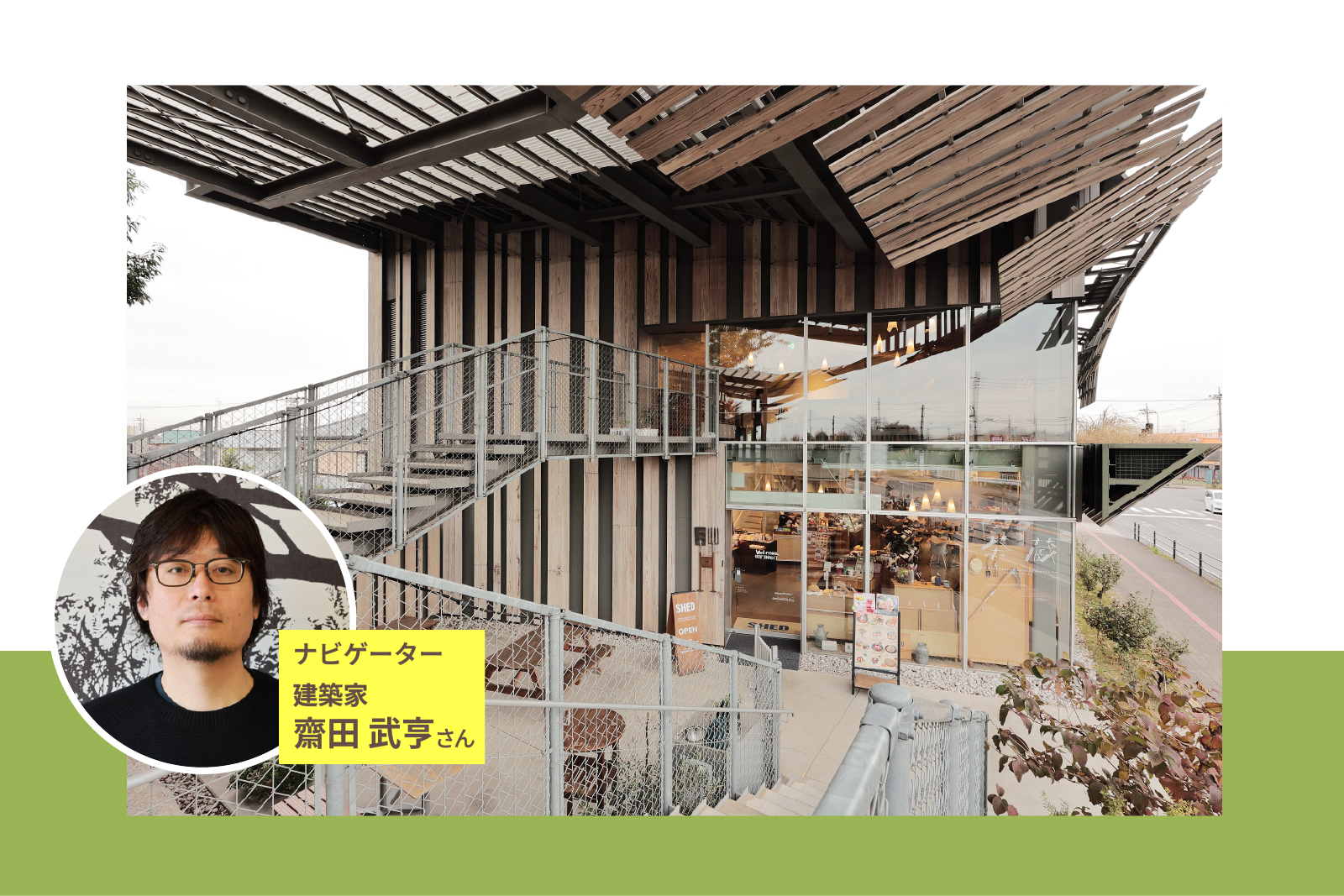

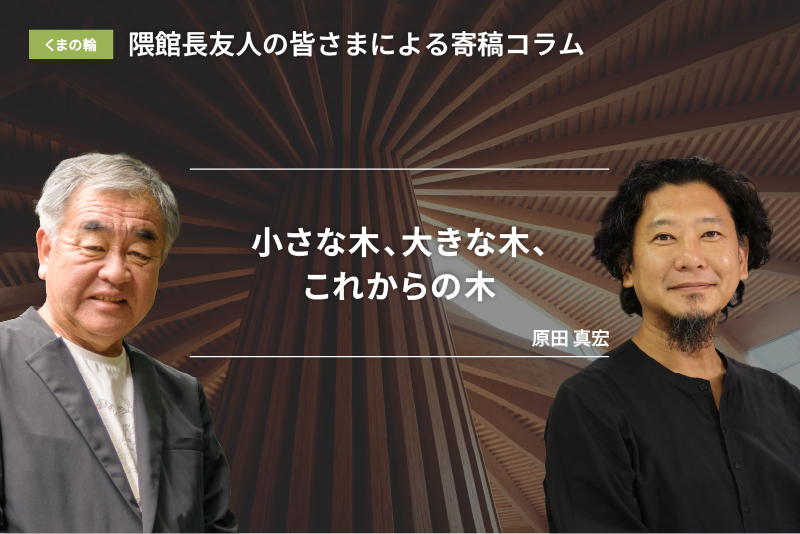

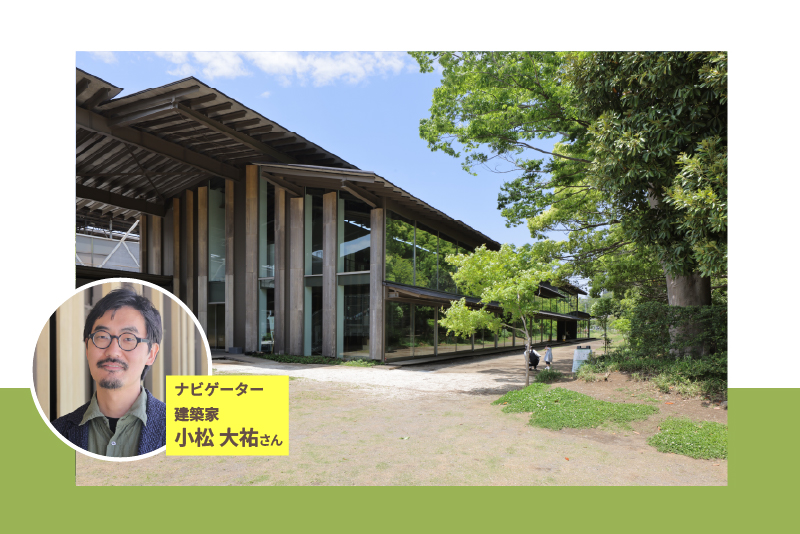

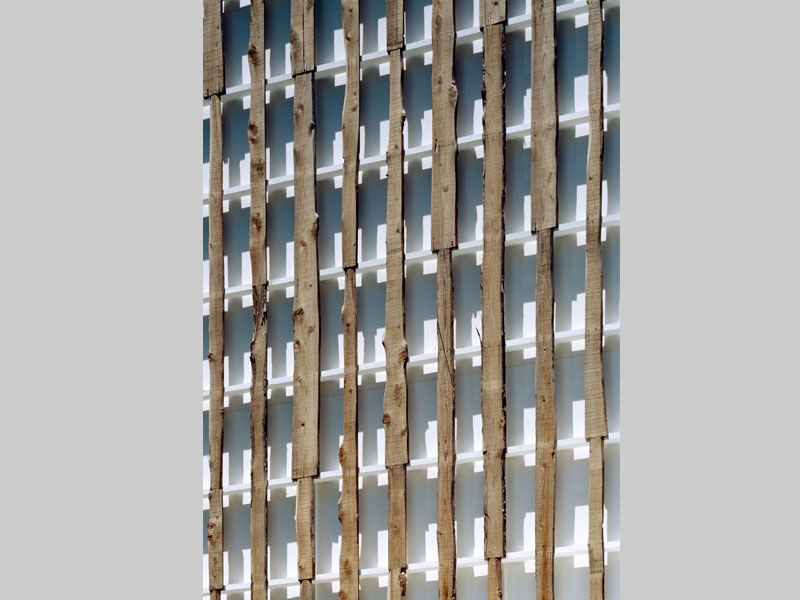

Illustration – the ethos of wood

The above exegesis is illustrated with two very different projects. Despite their totally opposite locations (periphery/centre), sizes (small/huge), use (private/public), aims (intimate/global), presence (modest/grandiose), they communicate the oneness of sensibility. That oneness is in the ethos of wood which makes Murai Museum and Olympic Stadium in Tokyo talk the language into which this initiative needs to be translated.

That juxtaposition is deep, cultural and historic, retrospective and prospective, future-orientated meditation in wood.

Post Scriptum

This essay has not attempted one logical question: what do we mean when we say –wood?

My suggestion is that everyone interested in this initiative sends a succinct answer, not longer than 3-4 words unless necessary. Those words might help us generate new questions. Wood in them will place answers in the right way. That might lead to new thinking and action, point at the ways and reaches of/for wood in the 21st century.

◎Click here for the answer submission form. The page transitions will be an email form in Japanese, so please use your translation function.

In inquiry form: Please select “others” in “category”. If you are a private, please enter “private” in “company name”.